This article was co-authored by Dr. Caroline Smith and Dan McTiernan and was first published in Permaculture Works journal which is a Permaculture Association of Britain publication. Dr. Caroline Smith is Senior Lecturer at Tasmania University and is co-author of Permaculture Pioneers — Stories from the New Frontier.

Most of us in the permaculture community cannot understand why not more people are attracted or interested in it. After all, it makes perfect sense to us because it seems to have many of the answers to Earth’s problems. On top of that, it’s empowering and gives us the tools to begin to make a difference straight away.

Bill Mollison called permaculture ‘uncommon sense’ and he was right. But why uncommon? How can we make sense of this? Integral Theory is one of the most useful approaches around for understanding why permaculture, while attractive to many, is still not part of mainstream culture. So, how can we think about extending its ideas and principles more widely? Let’s have a brief look at the theory before considering how it might relate to permaculture.

Integral Theory has been around since the 1980s. Developed by US philosopher and transpersonal psychologist Ken Wilber. While there are critiques of Wilber’s work, it provides a useful overview that can assist us to understand our extremely complex world, and to move beyond what Wilber believes is our defective worldview, of which the ecological crisis is the major casualty.

For Wilber, the universe is complex, ecological and evolving, and infused with spirit. In developing the theory, he drew from a wide range of global philosophies, as well as developmental psychology and evolutionary theories. He came to the view that everything is always in a state of development, equally applying to the evolution of the universe from the Big Bang to the present day and the emergence of life on earth, to psychological, social and cultural development and the evolution of consciousness in human individuals and societies. In permaculture terms, we could consider the Universe to be in a continuous state of nested succession.

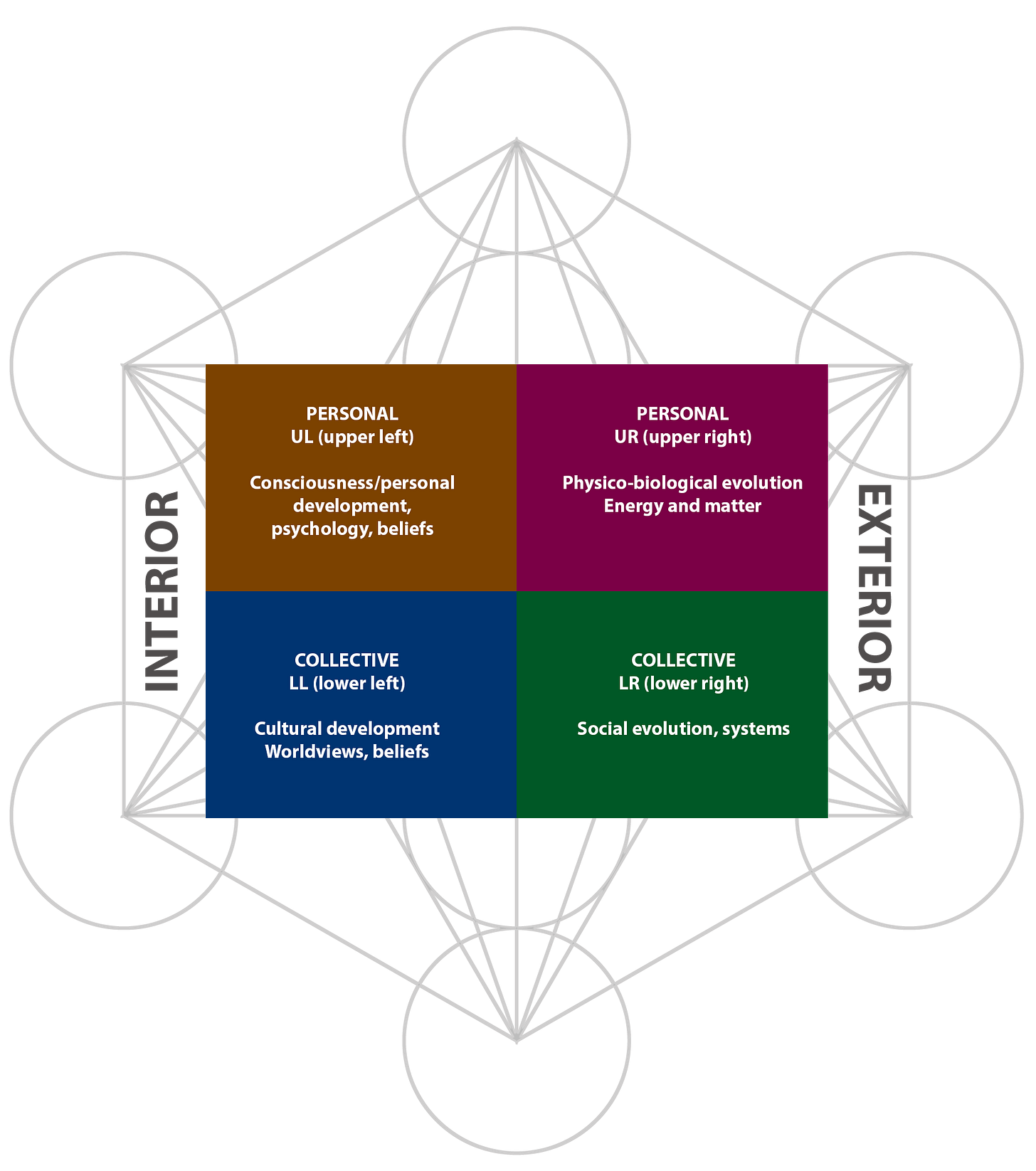

The four quadrants of reality

For Wilber, ‘reality’ consists of multiple perspectives that can be understood in four ‘quadrants’ that relate to the interior and exterior worlds as well as the individual and collective worlds. The two exterior quadrants describe entities that can be measured or observed, such as described by the sciences. Examples are the development of complex organisms from atoms and the development of complex human social systems from small hunter-gather groups. The two interior quadrants refer to our interior awareness, beliefs and worldviews, and describe the evolution of individual and collective consciousness. Wilber sees all quadrants as interwoven, with our individual sense of reality emerging from a vast background of cultural practices, languages and meanings.

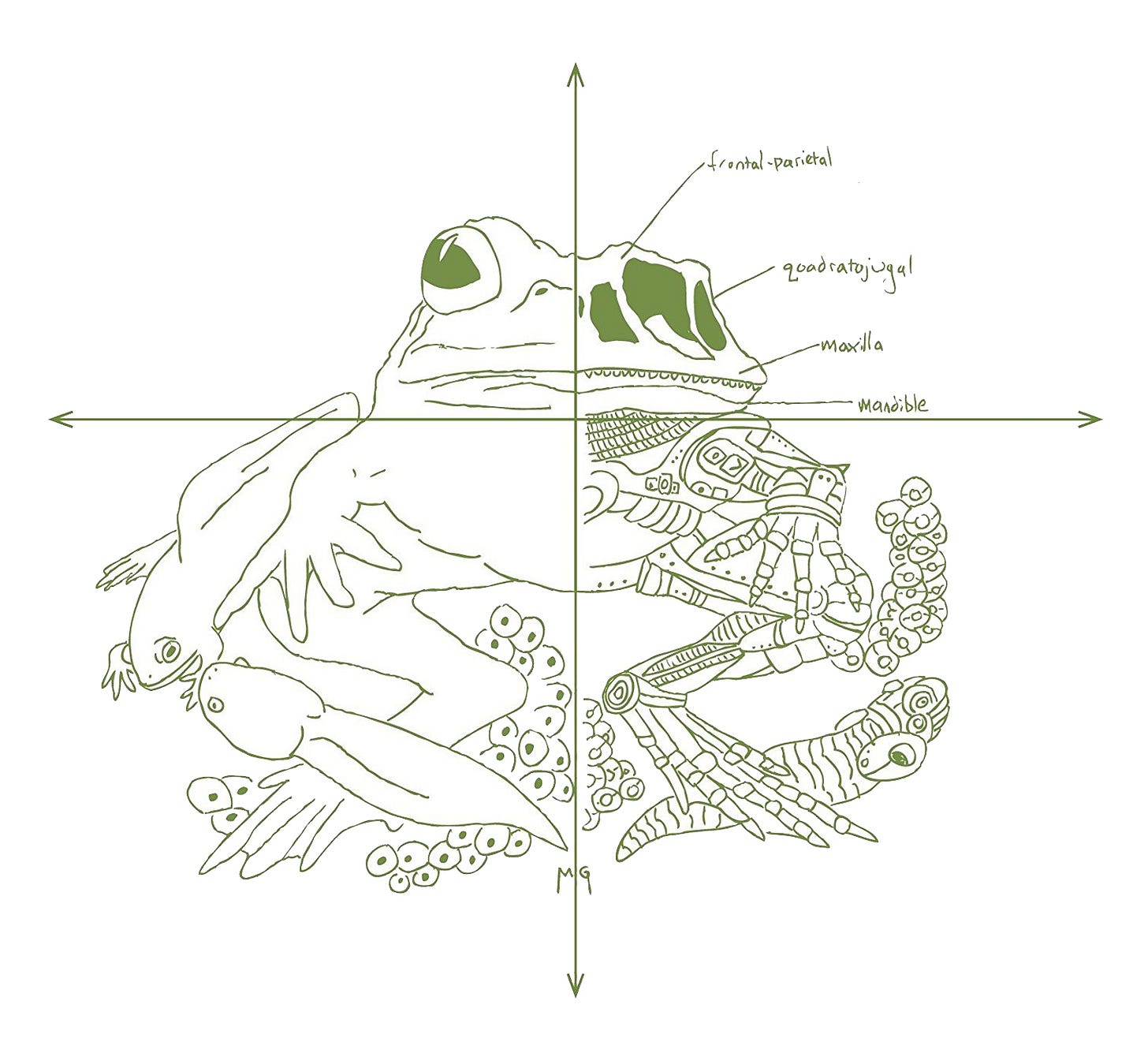

Esbjorn-Hargens and Zimmerman use the example of the ‘integral frog’ to illustrate this on the cover of their book Integral Ecology.

The upper left quadrant represents the consciousness of the individual frog, while the lower left represents frog culture - its relationships with other frogs. The upper right is our scientific descriptions of the frog – its anatomy, physiology and classification. The lower right represents the frog as a living system and as a component of an ecosystem.

For Wilber, development over the past couple of hundred years, and especially the ‘Great Acceleration’ since the second world war which has resulted in so much ecological damage, is because the focus has almost entirely been on development in the exterior (right hand) quadrants at the expense of the interiors. In our race for material and technological mastery, instead we have monoculture agriculture, pesticides and the green revolution while disconnecting from the more than human world. What is missing is any parallel development in our interior lives - a deeper sense of personal and cultural consciousness and a re-enchantment of nature.

In Wilber's words:

“We cannot build tomorrow on the bruises of yesterday... This means a new form of society will have to evolve that integrates consciousness, culture, and nature, and thus finds room for art, morals and science - for personal values, the collective wisdom, and for technical know-how.”

It is not that we should reject the exterior quadrants – science, technology and systems – they are critically important – but we need to balance them with interior elements that value our intimate relationship with the more than human world.

The principles and practices of permaculture include elements from all four quadrants and can be said to represent an integral approach. This may explain why it is attractive to so many - there’s something for everyone. Different permaculture practitioners emphasise some aspects over others – conflicts continue to rage as to whether permaculture is primarily a practical system for designing sustainable settlement (exterior focus), while others are equally adamant that permaculture emerges out of a spiritual practice, as suggested by The Druid’s Garden (interior focus). Integral Theory sees all views as important; they are just expressed in different quadrants, and practitioners afford them different emphases depending on their own developmental perspectives and values.

The four quadrants applied to permaculture

The ethics and principles of permaculture can sit comfortably balanced within all four quadrants if embodied holistically within our lives, but that is by no means a given. Take for example, the ethic of Earth Care. In the external - right hand quadrants, it becomes clear that the better we understand the scientific underpinnings of the water cycle or soil life for example, the more able we are to act in the best interests of the Earth. Likewise a deep and clear understanding of the systemic patterns of natural and industrial systems allow us greater capacity to design and implement more integrated and nature-aligned systems in the future.

But when we observe Earth Care through the internal quadrants lens we see clearly how our sociological and psycho-spiritual beliefs, norms and narratives are at the root of our relationship with the planet. If we act from the cognitive behavioural programming of the industrial growth model, we consider ourselves and everything else as separate, atomised, and the earth as a geo-mechanical phenomenon to be analysed and utilised for the increased socio-economic benefit of humans. Whereas if we step into an integrated indigenous or neo-indigenous internal relationship with Mother Earth, we know deeply that we are nature and that every thought and action we engage in has a ripple effect, because, at our most fundamental level, we are one with everything else. To act against the Earth is to act against ourselves and everything else and so there is no sense in thinking and acting in any other way than in the best interests of Earth.

It becomes clear then, that our ethics and principles are in direct relationship to the level of consciousness from which we are operating at, and that to fully inhabit the true spirit of permaculture we need to develop, mature and evolve all quadrants of our lives beyond the current industrial growth system.

Stages of development

The concept of development overlays and runs throughout all quadrants. Of particular interest to permaculture and to any attempt to understand why the whole world is not on board with us, is development in the interior quadrants. A number of theorists have considered this, the best known being Beck and Cowan, who developed the idea of Spiral Dynamics based on the pioneering work of psychologist Clare Graves.

Spiral Dynamics has a number of significant applications. For example, it was used in South Africa to help facilitate the end of apartheid and more recently it has been used in organisational systems theory such as in the work of Frederic Laloux. Spiral dynamics theorises that humans, whether as individuals or in societies, go through developmental levels or stages. These stages, also referred to as values memes, are paralleled with our worldviews - our values and beliefs systems that are adaptive and arise from our need to make sense of our physical and socio-cultural environment. They are the mental filters that provide the guiding principles for how we live, what we believe is important, and how we organise our lives. For simplification, the levels are often given colour codes. The table sets out the key attributes of each level and exemplars of that level.

As individuals, we tend to have a dominant value set that is adaptive for our particular context. As we develop our interior consciousness by learning, getting older and maturation, we are able to both transcend and include all the previous levels, but can access any of them when we need to. There’s no right or wrong level, only healthy, functional and unhealthy, dysfunctional aspects of each.

In the same way, in any society there will be a dominant worldview and belief system. For example, in so-called ‘developed’ societies, the current dominant worldview is mainly described by ‘orange’ modernism, where success and progress are measured in material wealth, and individualism is the prime ideology. The world is seen as a resource for humans to use and develop to make life better through science and technology, enabled by market capitalism. This worldview is thought to be held by about 50% of people in the US. During the Trump era, unhealthy aspects of the tribal red meme began to reassert themselves and challenge the orange orthodoxy of previous administrations. Interestingly, this tribalism manifested itself on both sides of the political spectrum. Under Biden, could we be seeing the beginning of a transition from orange to green values? It is very clear however, that unhealthy manifestations of the red meme, mediated by social media and fake news, still lurk near the surface.

The green postmodern worldview holds the values of harmony and cooperation, where we are all interconnected with each other and the more than human world. Permaculture aligns strongly with this, so those of us attracted to permaculture tend to hold the values and beliefs described by this orientation. However, it is the dominant value of only about 10% of people in Western societies, which may give us a clue as to why not more people are attracted to permaculture.

What seems to happen is that people with a particular value system tend to reject those of another, believing that they alone are right and reacting in a close-minded way to information that threatens their values. Unfortunately, we have all experienced this in the permaculture community, believing that our values are correct and all others are wrong. Like the inhabitants of other worldviews, we tend to live in our own tribal bubbles, communicating with like-minded others via our social media to reinforce our view of the world, often tying ourselves in knots grappling with identity politics and the less healthy aspects of woke-ism in the process.

Other unhealthy aspects of ‘green’ manifest in being judgemental and self-righteous. We’ve probably all been guilty of looking at someone with an ‘orange’ worldview thinking: “You greedy selfish capitalist! You’re good for nothing and totally destroying our planet! My totally non-violent self hates you!” Whereas, that greedy selfish ‘orange’ capitalist might equally retort with “You lazy tree-hugging, doley scum, feral hippy! Get a job and contribute to the economy!”

Internal development towards external change

Does this mean that we need to work harder at getting everyone to shift towards green values? In terms of caring for people and planet, yes! But clearly, the fact that the whole world has not adopted permaculture as yet shows this has not worked to date. Do we shout louder? Or do we wait until people’s values change - as they are doing, but far too slowly? Given the state of the planet, we do not have time to wait. We need a radically different approach, one of finding common ground, of recognising and attracting rather than marginalising people with other value systems. As psychologist Dan Kahan puts it, we need an approach that appeals directly to values that resonate with who people see themselves to be, rather than attempting to change their values.

Integral theory is useful here. It identifies ‘second tier’ values (teal/turquoise in the table), that acknowledge that every meme is partially right, and all healthy views must be honoured. As Wilber famously said, no-one is wrong 100% of the time. From a second tier view, the challenge for the permaculture movement is: how can we work for a sustainable future that honours the healthy elements of all values? One that looks after ecosystems (‘green’) but also builds a sustainable economy where everyone has meaningful work (‘orange’) and also has necessary rules and regulations and takes strong action when the situation demands it (‘amber’), has a global outlook (‘teal’) but is respectful and loyal to our local communities (‘red’)?

The permaculture community needs to keep having conversations with people who hold a range of value systems, respecting each other and seeking common purpose in ways that resonate for us all. It can begin with conversations that are non-judgmental about the future we want for our children that we all benefit from, particularly in our local communities. But the skill of generative conversation is one that needs to be relearned and the permaculture community has as much work to do in this field as the rest of society.

Daniel Schmactenberger, founding member of The Consilience Project, aimed at improving public sensemaking and dialogue, offers a simple yet elegant starting point which he terms ‘Rule Omega’. It starts from the premise that everyone, no matter how ‘wrong’, ‘triggering’, ‘idiotic’ (insert judgemental adjective of choice) they may seem to us, has something worth listening to. Some signal in the noise. And that rather than sticking to our reactive first impressions and closing our ears, Rule Omega asks us to assume that our negative judgement is based on our own ignorance and lack of understanding rather than theirs. So our job in a conversation is to give the benefit of the doubt by asking more questions, and by doing so, come to a more complete understanding of the other’s perspective. This does of course require good faith on both sides to evolve into a truly generative dialogue.

It has never been easy, and in today’s world we may be in danger of fragmenting into our values silos even further. But instead of seeing our values as binary opposites, Integral Theory gives us the concepts and tools to help us see them as many faces of the same issue - how can we all be better humans on our Mother Earth? Permaculture’s power is that it has the principles, ethical values, tools and know-how for that transition to happen if and when we bring our whole selves to it.

References

Beck, D. E. & Cowan, C.C. (2005). Spiral Dynamics: Mastering values, leadership and change. Blackwell Publishing.

Esbjorn-Hargens, S. & Zimmerman, M.E. (2010). Integral ecology: Uniting multiple perspectives on the natural world. Penguin Books.

Graves, C. W. (1972). Theory of Levels of human existence and suggested managerial systems for each level. In Beck, Arthur C.; Hillmar, Ellis D. (Eds.). A practical approach to organization development through MBO/Selected Readings. Addison-Wesley. pp. 168–181.

Laloux, F. (2014). Reinventing Organizations. Self published.

Schmactenberger, D. https://civilizationemerging.com/about/

Wilber, K. (1996). A brief history of everything. Shambhala.

Caroline was born in the UK and lived in South Africa for some years before moving to beautiful Tasmania. She has a background in plant pathology and has been a high schools cience teacher and teacher educator. She is currently working with the Pacific region training extension staff to run plant health clinics based on integrated pest management methods. Caroline has written extensively about the links between science, education, ecology and spirituality, and on permaculture, co-editing the book ‘Permaculture Pioneers’ with Kerry Dawborn. Caroline also ran an organically certified orchard and local food box scheme. She is locally active in the areas of permaculture education, food security and climate change.